Advance Layoff Notice Provision and the WARN Act

We find that the incidence of advance layoff notice more than doubled in the years following the passage of the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act. Geographic variation confirms that the act was likely responsible for this increase. We also find that state-level mini-WARN Acts that increased notification coverage had no discernible effect on the incidence of advance notice in these states. But the mini-WARN Act in New York that increased the required length of notice resulted in a commensurate increase in advance notice for affected workers.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

Introduction

A long history of research establishes that job loss tends to lead to a reduction in subsequent earnings and to other adverse outcomes. Intuitively, one expects that receiving advance notice of job loss could help mitigate these adverse effects. With advance notice, affected workers could begin their searches for new jobs or other plans earlier. These considerations motivated the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act, which took effect in February 1989. This law requires larger employers to notify affected workers at least 60 days before a potential mass layoff.1 The act’s purpose is to “provide workers with sufficient time to seek other employment or retraining opportunities before losing their jobs” (ETA, 2003).

Some early studies concluded that the federal WARN Act had little effect on the provision of lengthy written advance notice of layoffs of the type required by the act. In this Economic Commentary, we revisit this question and find that notice provision increased sharply a couple of years after the act went into effect. Moreover, the timing and magnitude of this increase in provision was geographically broad based, a fact which supports the idea that the federal WARN Act was responsible for the increased incidence. We also present additional analyses about state-level advance notice laws.

Previous studies

Researchers studied the efficacy of the WARN Act in the years immediately following its passage. Early studies addressed the question of whether the act increased the incidence of advance notice of impending layoff. In particular, Addison and Blackburn (1994) found that in surveys of workers who lost jobs, the fraction who reported receiving lengthy written advance notice—that is, notice of at least 30 days—did not rise in the first three years (1989–1991) the act was in effect. They therefore concluded that the act had at most a small effect on the provision of notice. Addison and Blackburn noted several reasons the act may lack teeth, although they find no strong evidence for any one reason in particular: Employers may not be aware of their obligations under the act; employers may choose not to comply because the act is enforced solely through lawsuits brought by workers who failed to receive the required notice; many layoff events are not covered by the act; and employers may structure layoffs to avoid coverage.

In contrast, the US Government Accountability Office2 (GAO, 1993) concluded that workers were more likely to receive the stipulated advance notice after the WARN Act took effect. Whereas Addison and Blackburn measured the incidence of advance layoff from a repeated survey of individuals who had lost jobs (the Displaced Worker Survey, described below), the GAO (1993) identified mass layoff events in 1990 from counts of claims for unemployment insurance in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Mass Layoff Statistics program. These were matched with a record of WARN notices filed in order to measure the fraction of employers experiencing mass layoffs who issued a WARN notice. The report compared this fraction with counts derived from a survey of establishments by the GAO (1987) that covers a period before the enactment of the WARN Act. The comparison reveals a substantial increase in the incidence of lengthy written advance notice. A later report indicated that this higher level of incidence persisted (GAO, 2003).

Data from the Displaced Worker Survey

We pursue the empirical strategy of Addison and Blackburn but extend the analysis to later survey years. As they did, we use data from the Displaced Worker Survey (DWS) supplements to the Current Population Survey (CPS), which is produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The DWS has been fielded biennially in January or February from 1984 through 2024. The target population includes individuals who recently lost or left their jobs because of a plant closure, insufficient work, or other similar reasons.3 The survey collects information about workers’ lost jobs and their current situations.

We use the surveys from 1988 through 2022. Beginning in 1988, the survey asks whether the worker received written notice at least one month (30 days) in advance of the job loss.4 We study workers displaced in the two calendar years prior to the survey year; for example, for the survey conducted in January 2022, we look at workers displaced in 2020 and 2021.5 Otherwise, we impose similar sample restrictions as Addison and Blackburn: we consider only those workers who were displaced by reason of plant closings or relocations, slack work, and elimination of shift or position. We exclude those employed in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries at the time of displacement and workers aged 61 years or more at the survey date. We also exclude a small number of DWS observations with missing values. The resulting sample comprises about 45,000 displaced workers.

Advance layoff notice in the DWS

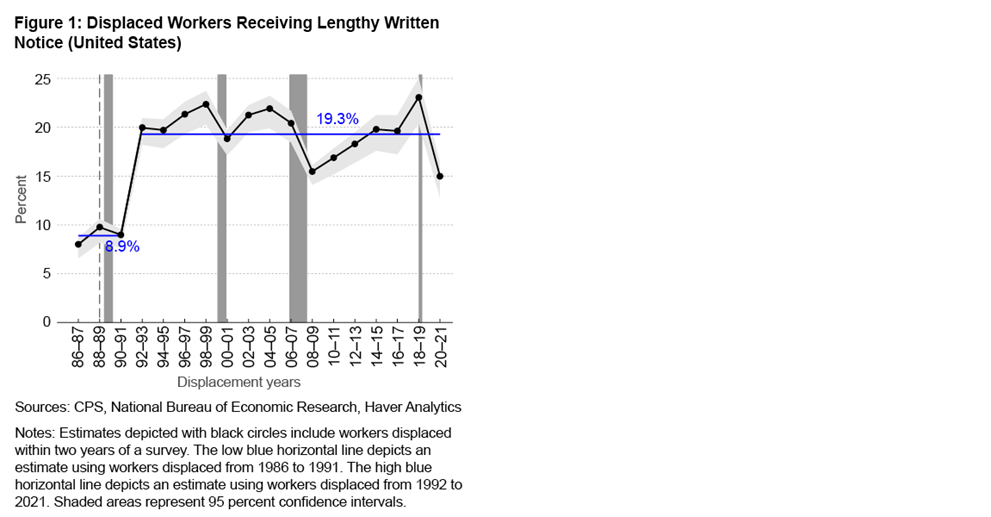

Figure 1 shows the percentage of our sample of displaced workers who report receiving written advance notice of at least 30 days in each two-year period. Given the requirements of the WARN Act, this measure should capture the bulk of notices issued under the act, although employers may also provide written notice for events not covered by the WARN Act.

We observe a sharp increase in the incidence of such notice between 1990¬–1991 and 1992–1993. Indeed, incidence more than doubles from about 9 percent to about 20 percent. This incidence remains at the higher level through the end of our sample period in 2022. Addison and Blackburn’s (1994) data end in 1991, so they were unable to observe this increase.6

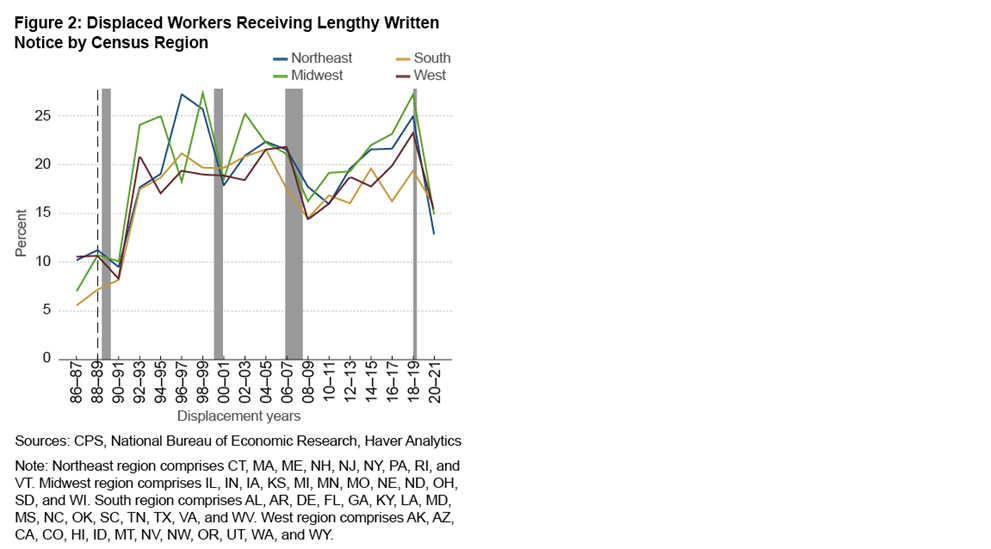

The implementation of the WARN Act is the most likely explanation for the increased advance notice provision demonstrated in Figure 1. Data by geographic region support this hypothesis. In particular, the increase in lengthy written advance notice can be seen across the country, and it occurs between 1990–1991 and 1992–1993 across different regions, as shown in Figure 2. The WARN Act passed in 1989 was federal, a fact which suggests we should see provision incidence rise across the country.

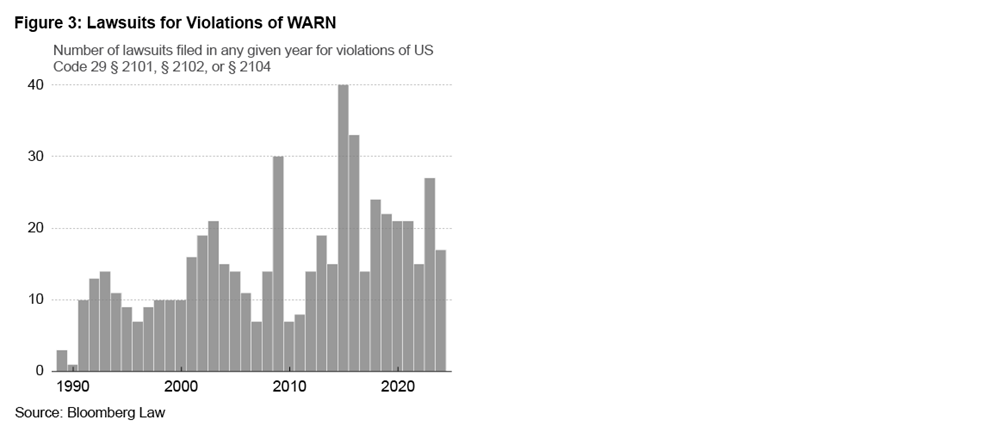

Why, then, did the WARN Act apparently not raise the incidence of notice in the DWS data until a couple of years after passage? While we can offer no definitive answer, we think it likely that two major factors were influential: unawareness or confusion about the requirement of the act and uncertainty about whether it would be enforced. On the first, the GAO (1993) noted that one-third of employers surveyed said that they were unclear or unaware about the provisions of the WARN Act. On the second, the GAO (1993) noted that few court cases had been filed between the enactment of the law and the report’s 1990 focus. Recall that the WARN Act is enforced only by lawsuits by workers. Figure 3 shows the number of lawsuits filed each year that appear to be over violations of the WARN Act. Few such lawsuits were filed in the first couple of years the law was in force, but the number started rising in 1991.7

State-level advance notice laws

Several states have enacted their own advance notice laws (“mini-WARN Acts”) in the wake of the federal WARN Act. In part, these laws expand the number of layoff events that require advance notice. For example, Illinois’ 2005 mini-WARN Act stipulated a smaller firm size necessary to trigger the notice requirement.

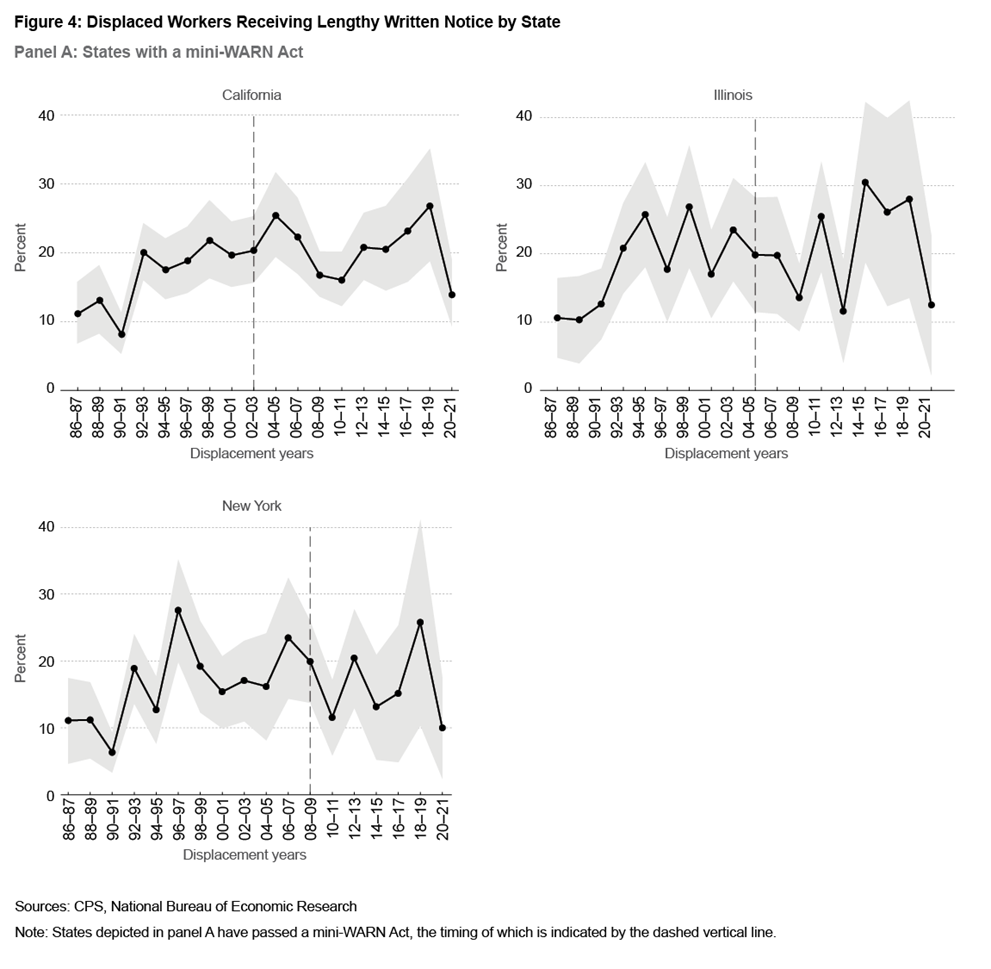

Mini-WARN Acts do not appear to have had a material effect on the overall incidence of advance notice, as shown in Figure 4. Panel A graphs the percentage of displaced workers in the DWS who report receiving lengthy written notice in three large states that enacted such laws.8 In each case, the vertical line marks the year in which the law took effect. For comparison, Figure 4, panel B shows the data for three large states that did not enact mini-WARN Acts. While all six states exhibit an increase in the incidence of notice in the rough vicinity of when the federal WARN Act took effect, none of the three states with mini-WARN Acts exhibits a compelling increase in the vicinity of when its mini-WARN Act took effect. This result is perhaps not surprising because the expansions of coverage in these laws were modest.

Mini-WARN Acts have been effective in other dimensions, however. Some also increased the length of advance notice required. Notably, New York’s 2009 law raised the duration of required notice from 60 days (as required by the federal law) to 90 days. To examine the law’s effect on the duration of notice, we turn to data on establishment-level WARN notices, collected by Krolikowski and Lunsford (2024).9

Figure 5 compares the median length of notice provided in WARN notices in New York to the median length in Illinois, whose mini-WARN Act did not increase the required length. Upon implementation of New York’s law in February 2009, the median length of notice in the state rose from close to 60 days to close to 90 days, and the higher level has been maintained since.10 We see no such increase in Illinois.11

Conclusion

Contrary to earlier research using worker surveys, we find that the federal WARN Act more than doubled the incidence of lengthy written advance notice. The increase took a couple of years, however, and we suspect that a lack of knowledge about the act and uncertainty about its enforcement may have delayed its impact. We further find that state-level mini-WARN Acts that increased notification coverage had no discernible effect on the incidence of lengthy written notice in these states. But the mini-WARN Act in New York that increased the required length of notice resulted in a commensurate increase in advance notice for affected workers.

Advance notice laws were intended to improve labor market outcomes for workers following displacement. A few recent studies have investigated the extent that these laws have been effective in achieving that goal. However, possibly because of the received belief that the federal WARN Act was not effective in increasing notice, they have concentrated on state-level laws or notice requirements outside of the United States (for example, Malik, 2023; Cederlöf et al., 2021). Now that we have established that the federal WARN Act did, indeed, substantially increase the incidence of lengthy written notice, we hope to see more research seek to understand the causal effect of federal WARN notifications on worker outcomes.

References

- Addison, John T., and McKinley L. Blackburn. 1994. “The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act: Effects on Notice Provision.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 47 (4): 650–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399404700409.

- Cederlöf, Jonas, Peter Fredriksson, Arash Nekoei, and David Seim. 2021. “Mandatory Advance Notice of Layoff: Evidence and Efficiency Considerations.” CEPR Discussion Paper 16387. https://ideas.repec.org/p/cpr/ceprdp/16387.html.

- ETA. 2003. “Worker’s Guide to Advance Notice of Closings and Layoffs.” Employment and Training Administration, US Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/Layoff/pdfs/WorkerWARN2003.pdf.

- Hernández-Murillo, Rubén, and Pawel M. Krolikowski. 2020. “Assessing Layoffs in Four Midwestern States during the Pandemic Recession.” Economic Commentary, no. 2020-21 (August), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202021.

- Krolikowski, Pawel M., and Kurt G. Lunsford. 2024. “Advance Layoff Notices and Aggregate Job Loss.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 39 (3): 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.3032.

- Krolikowski, Pawel M., Kurt G. Lunsford, and Meifeng Yang. 2019. “Using Advance Layoff Notices as a Labor Market Indicator.” Economic Commentary, no. 2019-21 (December), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-201921.

- Malik, Sara. 2023. “Without a Word of WARN-ing: Advance Notice of Layoffs and Labor Market Outcomes.” Manuscript.

- US Government Accountability Office. 1987. “Plant Closings: Limited Advance Notice and Assistance Provided Dislocated Workers.” HRD-87-105. https://www.gao.gov/products/hrd-87-105.

- US Government Accountability Office. 1993. “Dislocated Workers: Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act Not Meeting Its Goals.” HRD-93-18. https://www.gao.gov/products/hrd-93-18.

- US Government Accountability Office. 2003. “The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act: Revising the Act and Educational Materials Could Clarify Employer Responsibilities and Employee Rights.” GAO-03-1003. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-03-1003.

Endnotes

- See Krolikowski and Lunsford (2024) for a more complete description of the WARN Act. Return to 1

- The GAO Capital Reform Act of 2004 (31 U.S.C. 702 note) renamed what was previously the General Accounting Office. While the 1987 and 1993 reports cited in this Economic Commentary were published under the previous name, we use the current name here for ease of reference. Return to 2

- A worker who expects to be recalled to their most recent job within six months is not considered displaced. Return to 3

- Although 30 days is less than the 60 days required by the WARN Act, any increase in the incidence of 60-day notice would presumably also increase the incidence of at least 30-day notice. Return to 4

- The survey question asks about job losses in the three years before the survey (five years in the early surveys). Our two-year restriction avoids overlapping years across surveys. Return to 5

- The incidence in Figure 1 from 1986 to 1991 is very similar to the incidence of lengthy written notice documented by Addison and Blackburn (1994, Table 1). Return to 6

- The figure shows the number of lawsuits filed in each year for alleged violations of sections 29 § 2101, 29 § 2102, and 29 § 2104 that describe the main provisions of the act. Return to 7

- The limited sample size of the DWS requires us to concentrate on large states in order to have a sufficient number of observations to draw reasonable conclusions. Even so, the confidence intervals for these individual states are large. Return to 8

- State-level data on the number of workers affected by WARN notices are available at https://doi.org/10.3886/E155161. Return to 9

- Recall that there are exceptions to the duration requirement, and some firms may choose not to fully comply or to exceed the requirement. These factors account for the variability in the median duration in the graphs. Return to 10

- New Jersey increased the length requirement from 60 to 90 days in 2023. However, the data for New Jersey prove too noisy to draw definitive conclusions. Return to 11

Suggested Citation

Fallick, Bruce, Dylan C. Jacobs, and Pawel M. Krolikowski. 2024. “Advance Layoff Notice Provision and the WARN Act.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2024-18. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202418

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

- Share